“Many have expressed belief that this work has taken place in private, without informing the public. One core belief I have as an elected official is that local government only works when citizens participate. It troubles me greatly to think that so many feel they have been left out of the process.” — Commissioner Mark Ozias, Facebook, August 2019.

Thirteen months after holding a disastrous meeting to discuss Towne Road, the County is inviting the public to learn about the Dungeness Off-Channel Reservoir Project. The water storage facility will be constructed south of Sequim beside River Road, 20 miles east of the $350 million project that removed two reservoirs on the Elwha River a decade ago. The new reservoir will be above ground, with the Sequim Fault running beneath it. A manmade earthen dike will protect the community from the reservoir’s estimated half-billion gallons of water.

Residents were confused and suspicious after the County’s presentation about Towne Road in September last year. They had just been told that a county road designed, engineered, funded, and promised to be relocated likely wouldn’t reopen to public traffic. County staff and elected officials propagandized the benefits of converting the roadbed into a county park while suppressing crucial information that the County and Tribe had known for years: home insurance rates and emergency response times would increase if the road remained closed.

Unlike last year, when the public was prohibited from asking questions, this meeting will allow for community engagement. “Most of the time for the open house will be dedicated to questions and input,” emailed Steve Gray, Clallam County’s Deputy Director of Public Works.

Still, similarities between the new reservoir and Towne Road abound.

Same leadership

The Sequim Gazette featured a John Gussman photo in 2021 showing the leadership that restored the Dungeness floodplain and relocated Towne Road. Most of these faces and departments will be responsible for constructing the new reservoir. From left to right:

Department of Ecology’s (DOE) Joenne McGerr: As with Towne Road, the DOE is a partner and major grant contributor for the reservoir project.

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Randy Johnson (not to be confused with County Commissioner Randy Johnson): He told the media that if the County refused to construct the Towne Road Levee faster, the breaching of the Dungeness River dike would likely cause a mass casualty event. As the Tribe’s Habitat Program Manager, Johnson is a Dungeness Reservoir Work Group member. He also advises the County on which constituents deserve a voice, and which should be ignored.

Washington Recreation and Conservation Office’s (RCO) Megan Duffy: As with Towne Road, the RCO is another partner and major grant funder in the reservoir project.

Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Brian Phillips: Clallam County's website lists the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife as a reservoir supporter.

Puget Sound Partnership’s executive director Laura Blackmore: This organization co-authored the “Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Plan,” which determined that a reservoir was necessary.

Clallam County Commissioner Mark Ozias: His district is home to both projects. Against most of his constituents’ wishes, contrary to recommendations from emergency responders and against the advice of the County’s engineer and attorney, Ozias attempted to stop Towne Road from reopening ten times. Ozias’ attempts cost taxpayers significantly an aligned closely with those of his top campaign contributor, the Jamestown Tribe.

Cheryl Baumann, the North Olympic Lead Entity for Salmon’s (NOPLE) coordinator: She works under the County’s DCD department and manages tax-funded grants allocated by the State’s RCO agency. Baumann is prone to working against the County’s identified goals and she advocated for the closure of Towne Road. She also met privately with a landowner who wanted Towne Road converted into a private driveway.

North Olympic Land Trust’s (NOLT) Karen Westwood: NOLT is not identified as a reservoir partner but was criticized for taking a political stance with the relocation of Towne Road.

Mary Ellen Winborn: She headed the Clallam County Department of Community Development and is no longer in office. Her successor, Director Bruce Emery, will oversee the reservoir project.

North Olympic Land Trust’s Tom Sanford.

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Vice-Chair Loni Greninger: She may find herself increasingly in a leadership role with the announcement that Chairman Ron Allen, after 50 years, will retire at the end of his term. The Jamestown Tribe is listed as a project partner with the reservoir.

Tara Galuska is also from the State’s Recreation and Conservation Office (RCO).

Jamestown Tribe’s Natural Resources Director Hansi Hals has reasoned that breaching the dike was “usual and acceptable” but has declined to comment further on the event that unnecessarily cost taxpayers millions while achieving the Tribe’s stated goal of closing Towne Road. She is currently a member of the Dungeness Reservoir Work Group.

Clallam County Habitat Biologist Cathy Lear managed the relocation of Towne Road for a decade, organized the 2014 meeting that determined home insurance rates and emergency response times would increase if the road closed, and blamed the project’s defunding on soil contamination. Lear represents the County’s interests at Dungeness Reservoir Work Group meetings and is an executive committee member of the Dungeness River Management Team, which passed a resolution supporting the reservoir project.

This time, the City of Sequim will join project partners Clallam County and the Jamestown Tribe.

Before massive overruns, the Towne Road project was estimated to cost taxpayers $20 million. At an expected cost of $42 million, the reservoir project makes Towne Road look tiny in comparison — it involves bigger construction, bigger money, and bigger risks, too.

When asked about breaching the dike early, Hansi Hals replied that the Tribe’s actions were “usual and acceptable.” A new document has surfaced suggesting that the Tribe violated its own protocol.

The document, drafted by the Tribe, is titled, “Dungeness River Rivers Edge Levee Setback Project contract documents addendum #1.” It was issued on 5-28-21, a year before the Tribe breached the dike. It notifies subcontractors that, “The following revisions and clarifications are made to the Dungeness River- Rivers Edge Levee Setback Project Bid Documents. Please include a signed copy of this addendum with your bids.”

A year before the 2022 breach, the Tribe said that the existing levee (the Army Corps levee that held back the Dungeness River) “cannot be removed until Clallam County completes the lower river setback levee structure…”

The Tribe also said removing the dike could only be done if the County “had completed the lower mile setback levee to the point where the existing levee can be removed and authorizes the removal of the existing levee.”

While it’s unknown exactly how much the Jamestown Tribe’s deliberate breach of the dike cost the taxpayers ($6 million is a low number, and $13 million is a contractor’s estimate), Towne Road taught Clallam County a valuable lesson: The Jamestown Tribe communicates poorly, is willing to sacrifice transparency to achieve its goals, and has no accountability.

If the Tribe causes another blunder on such a large scale, it could bankrupt Clallam County and make our economically depressed region even poorer.

Same reasons and beneficiaries

Towne Road was relocated for the betterment of farms, fish, and people, which are the same reasons listed for making the new reservoir imperative. According to a 2021 Sequim Gazette article, Commissioner Mark Ozias supported Governor Inslee in advocating “for more aggressive work around climate change,” which made the road’s relocation necessary.

Ozias said in a Clallam County news release that designing the reservoir “represents a significant step forward on this critical project to address climate change impacts on our limited water resources.”

Both projects, Ozias assures, are necessary to fight climate change.

In addition to climate resilience, other benefits make reservoir construction necessary. Farms will benefit because irrigators can use the stored water during dry months. Fish will benefit because less water will be drawn from the river for irrigation during the summer. People will benefit because a 400-acre park will surround the reservoir with trails for hiking, birdwatching, and recreation.

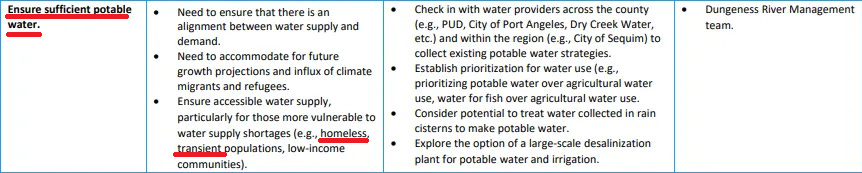

According to North Olympic Development Council (NODC) documents (a nonprofit led by its president, Commissioner Mark Ozias), the Dungeness River Management Team (a partnership between the Tribe and County) will ensure that the reservoir provides sufficient potable water for homeless and transient populations.

That may be why FEMA is supporting the project.

Same road relocation

Towne Road, which was never intended to close for one day, was closed for over two years due to the Jamestown Tribe’s breaching of the dike. Seven months after the closure, when its reopening seemed imminent, residents who had benefited from reduced traffic in their neighborhood submitted two petitions totaling 98 signatures asking for it to remain closed, and the commissioners halted the project.

River Road will likely be relocated for the reservoir. Towne Road taught taxpayers that the goals of a multi-decade, multi-agency, multi-million-dollar project can be derailed if fewer than 100 constituents petition county commissioners. In Clallam County, if a public road is temporarily closed, it may never reopen to public access.

Same soil contamination

While discovering contaminated soil under the old Towne Road was an unexpected expense, in February 2023, the DOE told the County that the cost of soil remediation would be completely reimbursed. However, months after the state agreed to cover that cost, it was still blamed for stalling the project.

In September 2023, Commissioner Mark Ozias was still emailing constituents about the cost of removing the dirt:

“…when it came time to put the road rebuild out to bid we had a significant uncertain cost related to the contaminated soil removal. None of the three Commissioners was comfortable moving forward with the project given this uncertainty as we did not have sufficient funding to pay both for a new road and for the additional remediation.”

The true reason that Towne Road’s completion had been halted was that the commissioners had received two petitions asking for the road to be closed. Still, Commissioner Mike French shared Ozias’ excuse seven months later:

“At the time the earlier decisions were made, financial concerns were much more influential – we had largely exhausted the grants that were originally going to pay for the road surface (due to the pollution remediation issues).”

In October 2023, eight months after learning the DOE would reimburse the County, the Sequim Gazette published this in an article:

At the same time, funding for roadways’ reconstruction dried up after the county found tons of contaminated material under Towne Road, costing about $1 million in grant funding for its removal, according to Cathy Lear, a biologist with the Clallam County Department of Community’ Development’s Natural Resources department.

“That’s the unfortunate reality of government; there’s rarely enough funding to go around,” Ozias said last week.

Blaming Towne Road’s funding uncertainty on soil contamination covered up the real cause of financial hardship: the County was forced to spend millions reacting to the Jamestown Tribe’s early breaching of the dike.

Like Towne Road, the reservoir site is contaminated. The historic “Sequim City Dump,” a ravine that collected garbage for decades, must be mitigated, and unforeseen expenses could trigger financial uncertainty. That unforeseen cost could become a scapegoat for other project hiccups not disclosed to the public.

Same consultant

The consulting firm that was paid millions to guide the County through Towne Road and the adjoining floodplain restoration project made hundreds of thousands for every change demanded by the commissioners and the Tribe. Shannon & Wilson will also lead the reservoir project and has already prepared a 119-page “Fault Hazard Evaluation Report” noting the risk of earthquakes and “surface rupture hazards” under the reservoir.

Same risk of mass casualty

The Jamestown Tribe’s Habitat Program Manager, Randy Johnson, said that if floodwaters had pushed through the premature breach, “Loss of human life would be a real possibility.”

Dungeness Meadows, a community of 195 homes, has already raised concerns about living in the shadow of the new reservoir. If the Jamestown Tribe were to rupture the levee holding back the reservoir, a 30-foot-high wall of water could sweep 350 residents downriver.

Every resident downriver from the reservoir should be concerned. A torrent of water would knock homes off their foundations, and in the Tribe’s own words, “News helicopters would circle the devastation and speculate on the number of dead.”

Farmers

Farmers in the Sequim-Dungeness Valley are in a tough position. They have closely monitored what happened in Oregon and Northern California’s Klamath Basin, where irrigators with water rights dating back to the 1880s were only allowed to draw 15% of what was needed from their reservoir. The restrictions were put in place to protect the sucker fish, a key species to the heritage of the Klamath Tribes in southern Oregon, and to save the salmon, which are revered by Northern California’s Yurok Tribe.

Those restrictions crippled crop production and drastically changed the region, which, like our area, is known for fertile soil. Crops that produced several thousands of dollars per acre in income dropped to yield only hundreds per acre. Restaurants, stores, and schools shuttered as farmers gave up agriculture and moved out of the Klamath Basin.

Sequim area farmers support the new reservoir, which will supply irrigation to their crops via a network of ditches and pipes. The Jamestown Tribe is pushing a project to convert Sequim’s historic irrigation ditches into pressurized pipelines, which the Tribe says must be done to conserve water. Property owners say their wells are drying up as the ditches are piped, and wildlife and greenway corridors are being lost. They also say the pipelines are being installed without landowner permission or proper easements.

Jamestown Tribe’s CEO Ron Allen addressed the piping project in a letter to the editor featured in the Sequim Gazette. He called the pioneer families who have farmed the area since the 1800s “newcomers” and said that the Tribe has worked with neighbors and communities “Instead of fighting in court.” He also said, “We have been an example to others seeking a constructive alternative to litigation.”

Farmers are understandably nervous. Their hesitation to embrace the new reservoir or reluctance to pipe the ditches might lead to a legal battle that could end their way of life. For now, the Jamestown Tribe has made a request, but it seems poised to sue if necessary.

The Whatcom outcome

Farmers and Tribes are closely watching unprecedented developments in Bellingham, Whatcom County, and the Nooksack River watershed.

Locally, the “Dungeness Water Rule” was adopted over a decade ago. It’s a theory that every drop of water from wells in eastern Clallam County depletes the Dungeness River, thus infringing upon the Jamestown Tribe’s treaty rights to harvest salmon. The Tribe partnered with the Department of Ecology to implement the Water Rule, and that’s why new residents must pay a mitigation fee and install water usage monitors on their private wells. The metering of water usage for tribal properties is exempt from the mandate.

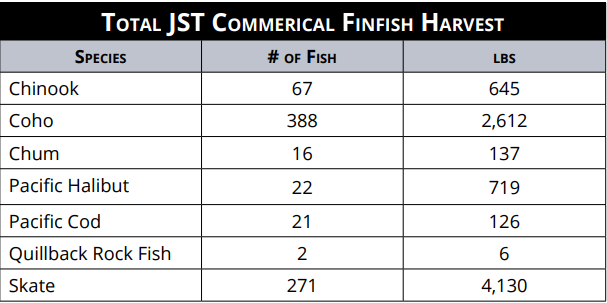

Saving the salmon has measurable benefits for the Tribe. According to the 2023 annual report, the Tribe of 519 members (217 of whom live locally) harvested 3,394 pounds of salmon last year.

The Nooksack and Lummi Tribes are testing the legal waters but taking things a step further.

Citing their cultural connection to the water, tribes near Bellingham are making a legal argument that every drop of groundwater (like the Dungeness Water Rule) and surface water (lakes, tributaries, and the Nooksack River) legally belongs to the Tribe.

The Washington Department of Ecology filed a general adjudication for the Nooksack River system in May. Adjudication is a lengthy process that determines who has legal rights to water, how much water can be used, where it can be used, when it can be used, and what it can be used for. Adjudication determines water rights by seniority, and Tribes contest that their water rights were granted by the treaty of 1855. This could strip century-old irrigation rights from users, legally and permanently determining water rights for all residents. 30,000 water users in the Nooksack River Basin may be forced to install meters that measure and restrict water on their existing private wells.

The consensus is that Washington State’s current leadership and political climate would support adjudication and reallocating Whatcom County’s water rights to the Nooksack and Lummi Tribes. If adjudication was filed in Clallam County, the Jamestown Tribe could reassign control of the reservoir’s water. Irrigation shares and water rights determined 130 years ago could be scrapped. This explains why farmers are willing to appease the Tribe, even if that means installing pipelines that violate private property rights. They’d rather compromise with the Tribe’s demands than risk an expensive court battle with an uncertain outcome.

If Washington State were to adjudicate water rights in Clallam County, water usage on sovereign nation land, such as the Jamestown Tribe’s casino, hotel, and golf course, would be exempt.

Tuesday night’s meeting

It’s more than a meeting about the fault lines snaking beneath the proposed reservoir site. It’s about two troubled partners hoping for a different outcome after a failed collaboration. One, the Jamestown Tribe, represents the interests of 217 residents, lacks transparency, and has proven it will endanger the greater community to achieve its goals. The other, Clallam County, which represents 77,160 residents, has shown that private, political, personal, and special interests are prioritized over public interests.

It’s a partnership where one party can make mistakes without accountability, and the other will cover them up and pay to fix them.

What could possibly go wrong?

County open house about the Dungeness River Off-Channel Reservoir

This Tuesday, October 22nd, 6 to 8 pm

Guy Cole Convention Center (Carrie Blake Park)

202 N. Blake Avenue, Sequim

Thanks Jeff. keep up the FIGHT. I wonder why Noah decided to build an Ark, when he could have just raised taxes to affect climate change?

A fault line under a reservoir. A 30 foot high wall of water. The recurring theme is just "wash away those pesky residents." And the bumper sticker politics to push the project along, "Climate Change".