It all started with enough baby wipes and feminine hygiene products to fill a trash bag.

"I could see right away what the problem was," said Anita Pruvell as she recalled opening the septic cap at one of her rentals. "The intake was clogged with stuff you aren't supposed to ever flush down the toilet."

Pruvell had arrived at the rental property she owned after her tenant had notified her that the septic alarm was sounding. Pruvell told the tenant that she would need to pay the cost of pumping the septic tank since she had been using the system irresponsibly. A disagreement ensued, and Pruvell set to work removing the debris that clogged the pump chamber.

What Pruvell didn't know was that the tenant videoed Pruvell while she worked on the overflow and sent the footage to the County. Months of headaches, miscommunications, jumping through hoops, and paying fees were about to begin for Pruvell.

Anita Pruvell isn't the property owner's real name. She’s convinced that one county employee is targeting her unfairly and may retaliate further, so she's asked that her name and property information not be disclosed. She has lived in the Sequim area since the 1980s and owns multiple properties, most of which are rentals. She has worked in real estate and construction and is more familiar with county code than the average resident.

Pruvell doesn't deny the "illegal septic pumping" violation for which she was cited after the video was reviewed by the County. Still, she says her actions were necessary to unclog the pump and return the septic system to working order until a pumping could be scheduled. However, within days of the reported violation, a site visit was conducted by County Environmental Health Specialist J. Reed — a county employee Pruvell says she had been dealing with for 13 years.

Pruvell says she'd had three other interactions with Reed over septic issues, and each time, Pruvell was met with resistance. Pruvell says her interactions with Reed have been unpleasant.

Pruvell says she received a letter after Reed’s site visit. The letter directed that both septic systems on the property be inspected by a licensed designer. The septic belonging to the main house (that had overflowed) passed inspection, but the septic system of a smaller residence called an Accessory Dwelling Unit, or ADU, did not.

Pruvell received a second letter directing her to have the ADU septic repaired, and she complied. She invested thousands in septic inspections, pumping, test pit digging, and designing, all of which were routine. A test pit was dug with perk holes while a county environmental health specialist observed. Pruvell’s licensed septic designer and his team also attended. Things seemed to be going smoothly.

Pruvell received a third letter, this time from County Code Enforcement. They determined that the ADU was too big per county code — it needed to be half the square footage of the main house, but it exceeded that size. It was also unpermitted. Pruvell was shocked because both the primary house and ADU were built in the 1920s when no code or permit was needed. Pruvell was instructed to get a list of permits from the building department.

The 1920s small house wasn't considered an ADU because it had been mistakenly permitted on documents as a "shop" in 1997. Still, the Assessor’s office has taxed the ADU as a house since 2003, and it is labeled “house #2” on the County Assessor’s website.

Since the smaller house exceeded 50% of the primary home's square footage, it was too large to be an ADU. It would either have to shrink, or the primary house would need to expand — there were permits and fees for that, too. The County mandated that the renters be evicted from the smaller house within six weeks, which Pruvell did just after the holidays.

Pruvell spent late 2023 and early this year visiting the county up to three times a week, working with Environmental Health, Code Enforcement, the Building Department, and the Department of Community Development. "Too many fish were in one bowl," Pruvell said. "No department knew what the other department was doing, and I was getting the runaround."

In the meantime, to satisfy the County's demands, Pruvell entered into a Voluntary Compliance Agreement (VCA). The 13-page document placed additional demands on Pruvell:

A new septic system for the small house needed to be installed.

The old septic system needed to be pumped, crushed, filled, and decommissioned.

A Change of Use permit application (and fees) needed to be submitted for the small house.

Before and after floor plans for both residences needed to be provided.

A scope narrative and engineered plan plus calculations from a certified engineer needed to be provided.

A Change of Use permit application (and fees) for the covered porch and laundry room of the primary residence needed to be provided.

A Well Site Verification and Water Availability Application for the 2003 well needed to be completed.

The State Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation needed to be contacted to approve the plans.

The agreement seemed daunting, but Pruvell began the laborious task of addressing every item. She began to wonder if she was being targeted or treated unfairly.

Environmental Health denied the septic permit application, citing that having an ADU on the same property as the primary residence was a violation. Pruvell, who had thought that entering into the Voluntary Compliance Agreement was a path toward approving the septic permit, wanted to appeal the decision. The fee to hold a hearing was $265 dollars, which she paid.

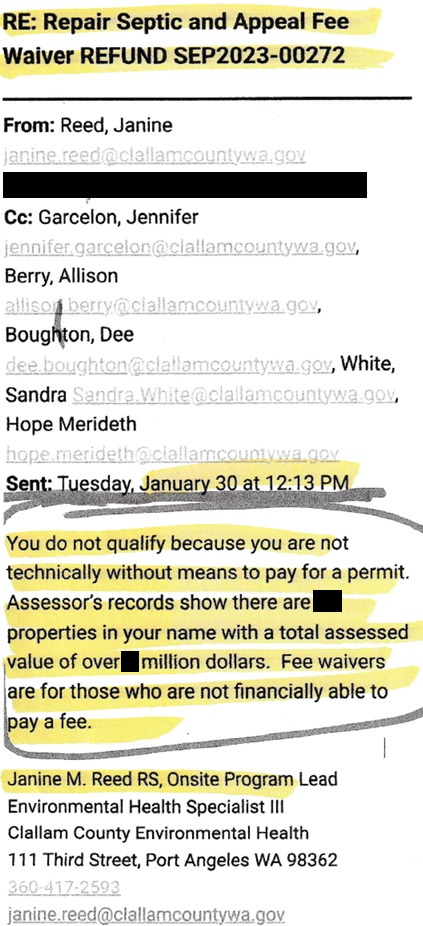

Pruvell asked about a "Public Health Fee Waiver Program," and Reed sent additional information. Reed's email indicated that Pruvell may qualify for the "Financial Hardship" category if she provided her IRS 1040 Tax Return, which Pruvell did.

Pruvell’s IRS 1040 showed she had a loss of income, which easily met the qualification. However, Reed denied the waiver:

The Fee Waiver Program does not state that requests will be denied based on the number of properties or their value.

Pruvell had endured a rough year as a landlord in Clallam County, and her tax return showed it. There were damages to repair and pay for, upgrades to fund, and problem tenants.

One renter quit paying Pruvell, so together, they formulated a plan to keep him living in her rental. The tenant contacted Serenity House of Clallam County, a local organization that provides housing resources. The organization, Pruvell, and the tenant agreed on a plan in which the tenant would not be evicted, and Serenity House would pay the tenant’s rent to Pruvell monthly. The program would begin after 90 days, but Pruvell had to agree not to evict the tenant in the meantime.

At the end of 90 days, Pruvell contacted Serenity House only to learn that the program had ended. She had lost four months' rent.

Pruvell spent the first half of 2024 planning for the ADU’s new septic system. She applied for the permit to the County, paid the fee, and submitted plans from a licensed septic designer. The permit was denied again. The design was satisfactory, but the plan had to be moved 25 feet east. Pruvell's property allowed ample room for that minor change, so she began getting estimates — Pruvell wanted work to begin the moment the permit was approved.

On May 2nd, J. Reed sent the following email to over 30 local contractors known to perform septic installations, Pruvell was not copied on this email:

Soliciting bids for work prior to issuance of a permit is not illegal, against the rules, or uncommon. Contractors routinely provide estimates that state, "contingent on there being no changes upon final approval." Home builders review blueprints and prepare estimates for clients before building permits are issued; this is no different.

Professionally, Reed's distribution of this email has interfered with Pruvell's right to do business. Personally, Pruvell is at a loss as to why the County would take this step after she has worked so hard to meet their legal requirements.

It's impossible to assign a cost to the time Pruvell has spent driving to the courthouse, visiting different departments, calling and emailing permit issuers, and double-checking their work. She estimates she has paid $10,000 in fees and the hiring of licensed professionals during the permitting process. She says she has lost over $22,000 in rent while a vacant property awaits the County's approval. She still faces the $40,000 cost of installing the septic system once it is approved.

Pruvell is the first to tell you her tenants aren't high-earners — these are often people on fixed incomes. As a single mother of four kids, the youngest still in elementary school, Pruvell has a soft spot for hard-working people who struggle to make ends meet. She sees herself in many of these tenants, and she remembers that before she became a property owner, people recognized her strong work ethic and gave her a chance.

Renters recently moved out of a property Pruvell purchased seven years ago, but you'd think it was new construction — granite countertops, soft-close cabinets, a custom tiled shower. "This is going to be an Airbnb," Pruvell said of the recent upgrades. Having a short-term rental might mean more work for Pruvell; she’d have to clean it after every guest. An Airbnb would be more work, but it would be safer because managing long-term rentals and dealing with the County is a headache… an unfortunate outcome that will contribute to the region’s housing shortage.

Pruvell pays tens of thousands of dollars yearly in property taxes but is convinced the County doesn't work for taxpayers. Her tax dollars fund our roads, schools, libraries, and even programs like Serenity House, which shorted her thousands of dollars in missed rental income. Pruvell isn't going anywhere; she knows how to adapt and isn't afraid of hard work — even if that means fishing baby wipes out of a septic tank.

When asked what advice she would give to anyone else feeling overwhelmed by the County's permitting process, Anita Pruvell said, “Perseverance is key, and don’t do anything until you get it in writing.”

Update

Clallam County Watchdog contacted Environmental Health Specialist Janine Reed, Health and Human Services Director Kevin LoPiccolo, and Department of Community Development Director Bruce Emery for comment. Director LoPiccolo responded:

The Public Health Fee Waiver Application is outlined in the County’s Board of Health Policy #500.4. The policy does not mention “other indicators of income/assets that the county reviews” apart from the IRS 1040 Tax Return supplied by Pruvell.

LoPiccolo says the applicant “appears to believe the septic permit was denied,” but Pruvell says that is untrue. Pruvell says she signed the Voluntary Compliance Agreement prior to Environmental Health’s denial. The Department of Community Development denied the permit because the designed septic system needed to move 25 feet further east. This automatically triggered Environmental Health to deny the permit due to the code and permit violations that had already been resolved under the VCA.

After reading LoPiccolo’s response, Pruvell said, “The departments do not communicate with each other, even though they share the same front desk. Nor do they acknowledge what the Assessor believes is a house when the DCD and Environmental Health believe it is a shop.”

Wow! This is very concerning. Having a property owner trying to do the right thing and this happens? One would think the county should be happy to be working with a willing participant.

I just looked at the county's OSS compliance page. Their Red to Green Program has made progress, but seems to be occurring quite slowly. Compliance in the high priority Marine Recovery Area (MRA) is at about 40%. The goal was 60% by 2020. Let's agree that's a failure. So, why isn't there more effort to accelerate compliance? Seems to me all the time spent with this one site could have produced more progress with MRA and countywide compliance.

Is it too late for her to tell them she’s an illegal & this is a sanctuary city, county & state? She can then get free tax-payer money, be left alone & squat as many homeless do without any repercussions.