“It is disappointing that a small number of landowners are obstructing the process.”

While these words may appear to address the weekly courthouse discussions regarding whether to complete Towne Road as designed and funded, they pertain to current community issues surrounding Sequim’s irrigation canals and the reorganization of one irrigation company. The words belong to Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe CEO and Chairman W. Ron Allen and were published by the Peninsula Daily News in an op-ed. Both matters, Towne Road and the piping of Sequim’s original irrigation ditch, share similarities.

Nearly 130 years ago pioneers recognized that the fertile Sequim-Dungeness Valley was too dry for sustainable agriculture, so they created a network of irrigation canals. With the introduction of water from the Dungeness River, the dry prairie flourished and every May the completion of Sequim’s first ditch is celebrated during Washington State’s longest-running festival. This year, the 129th Irrigation Festival will be celebrated May 3rd through 11th.

For generations, landowners in eastern Clallam County’s irrigation districts have been taxed or assessed to pay for the upkeep of canals in exchange for irrigation “shares”. These shares and water rights still exist and are attached to property titles. Landowners are still required to pay the tax or assessment.

To manage and maintain the valley’s different canal systems, irrigation districts and companies were created. One such irrigation company, Sequim Prairie Tri-Irrigation Association (SPTIA), announced on January 30th, 2023, that it would undergo a three-year project to remove Sequim’s original irrigation ditch and replace it with a piped system. Some SPTIA irrigation shareholders objected and said that they had not been informed and had not consented to the ditch on their property being removed.

Those opposed to the piping project referenced SPTIA’s bylaws which stated that the irrigation company “was formed for the purpose of diverting water from the Dungeness River and carrying the same in its ditch and distributing the water to its shareholders for the purpose of irrigating their lands… the ditch is an open ditch, except for several siphons and culverts.” In addition to piping concerns, shareholders questioned whether the current easement allowed for the removal of the ditch.

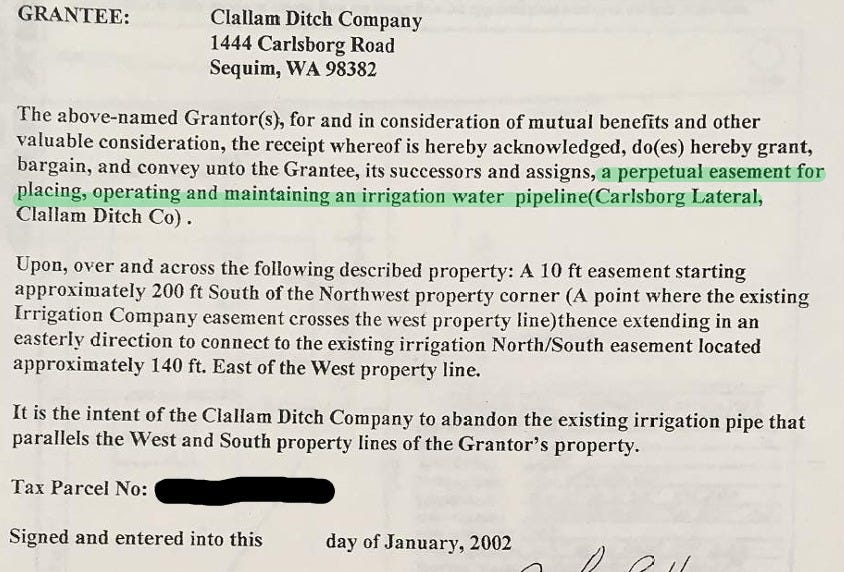

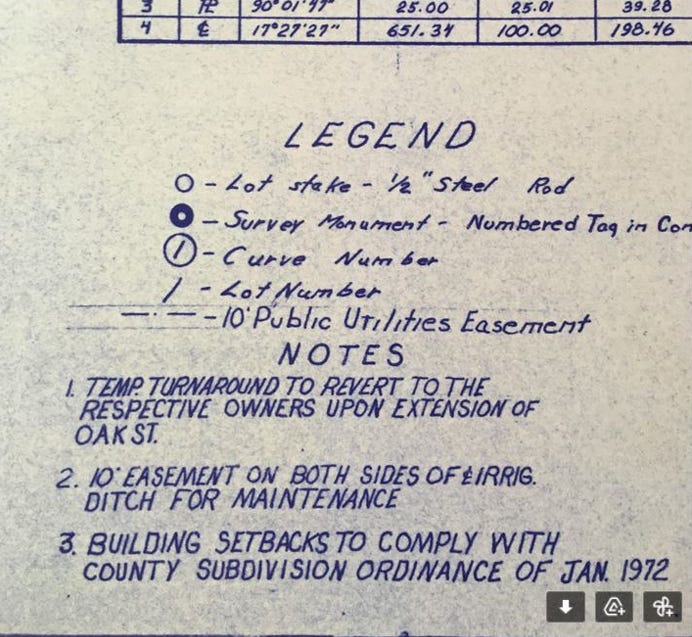

To upkeep these irrigation ditches, maintenance easements were granted along both sides of each canal. In Sequim, it would be typical to see a “ditchwalker” crossing through private properties, via the easement, to clear weeds, branches, and other debris from the canals. Below, a property’s ditch easement is outlined as being 10 feet on both sides of the ditch.

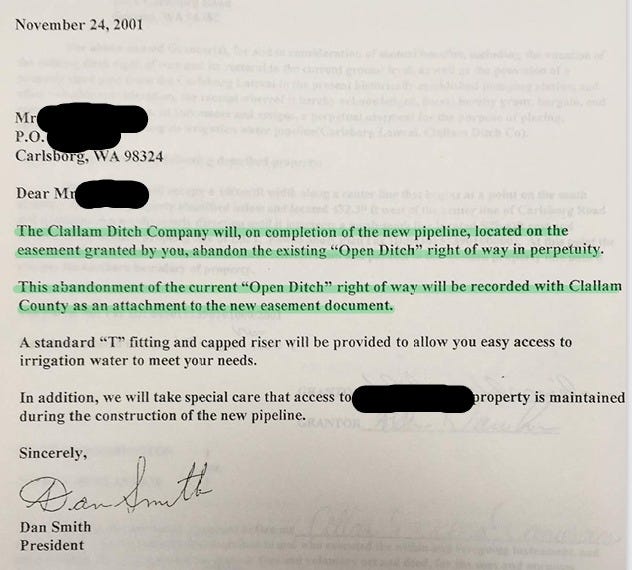

Shareholders argued that current easements do not allow for the removal of a ditch and installation of a pipeline. Without modification, the easement does not mandate that a property owner allow the heavy machinery that would be necessary to install and perform routine maintenance on the irrigation pipe crossing their property.

Many SPTIA shareholders were concerned that once the water quit flowing through the ditches, a century-old wildlife corridor through Sequim would be lost. Without water, vegetation could weaken or die, and the tree canopy would disappear. Habitat for frogs, bats, owls, waterfowl, eagles, birds of prey, foxes, deer, and even bobcats would perish forever. Bald eagle nesting sites were threatened as were stands of Garry Oak – Washington’s only native oak species that is both slow-growing and protected. Many shareholders who had already undergone piping were losing mature trees on their property and had to remove them at substantial cost.

Another concern, realized by various residents near the canals, was that some wells were going dry. With Sequim’s rainfall averaging only 16 inches per year, the ditches had played a role in charging aquifers since 1896. Without water seeping into the ground, private wells were at risk of drying up. Drilling new wells, or connecting to a municipal supply, came at a steep cost.

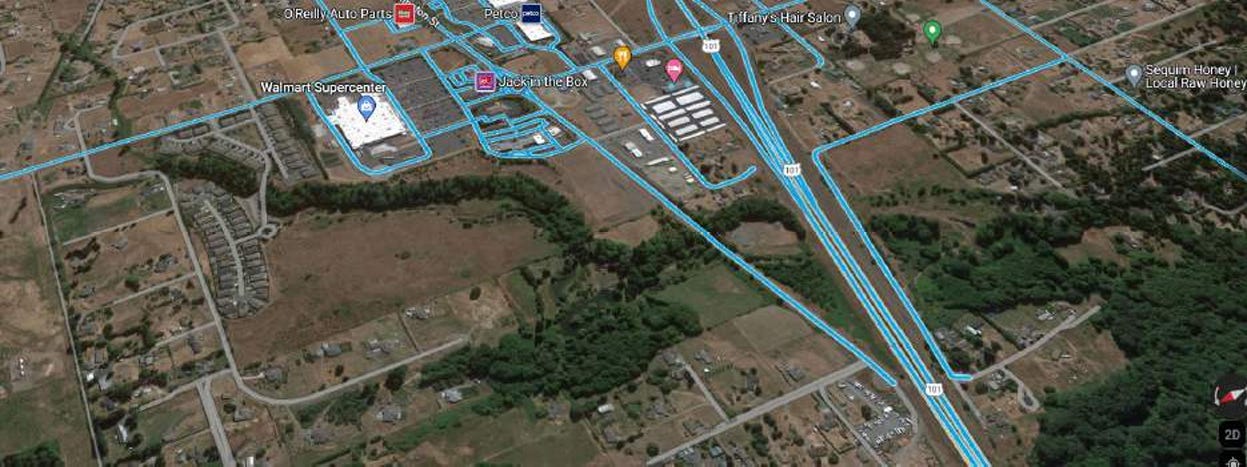

The ditch currently targeted for piping runs west of Walmart, through Jennie’s Meadow, under Priest Road, and east through residential neighborhoods.

Shareholders requested documentation of mitigation measures that addressed the disruption of bald eagle habitat and the loss of Garry Oak groves. They requested a review of the construction permits, contracts, and piping easements that had been granted to the Clallam Conservation District (CCD) — a county agency that had already assisted in piping over 66 miles of irrigation ditches. As of December 2023, shareholders said they still had not received the documents that had been requested from the county.

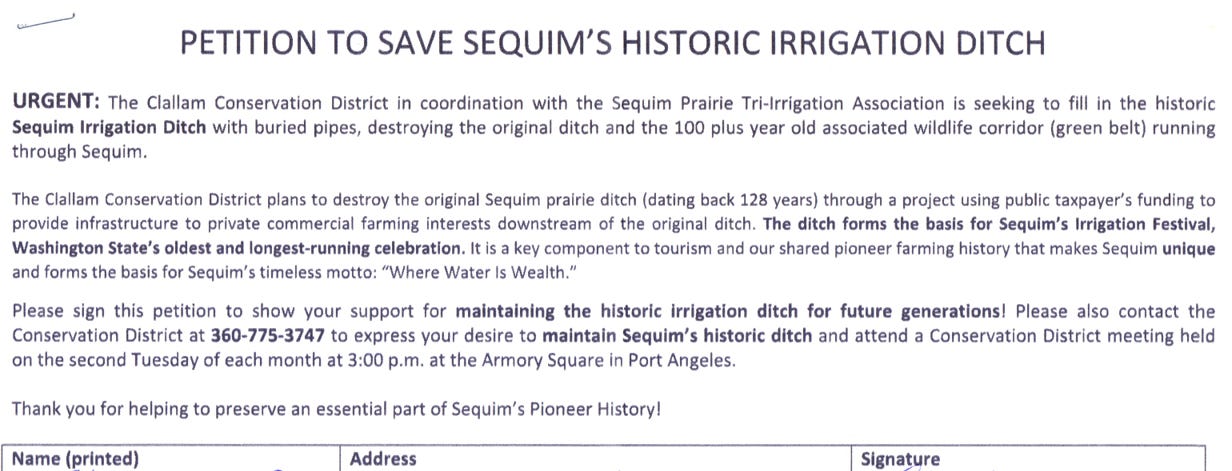

Similar to Towne Road, shareholders and neighbors submitted a petition to the county commissioners. Those who have closely followed the Towne Road debacle will remember it took only 98 signatures to halt the completion of a multiagency, decades-long, $20 million project. The residents asking to maintain Sequim’s historic ditch submitted 121 signatures.

Shareholders told the commissioners that pressurizing irrigation water brought risks. In 2007 two workers were inspecting a pressurized irrigation pipe when one worker reached down to move a riser cover. That small motion triggered the assembly to explode upward into the inspector’s head. Both workers were hospitalized, and one suffered a traumatic brain injury.

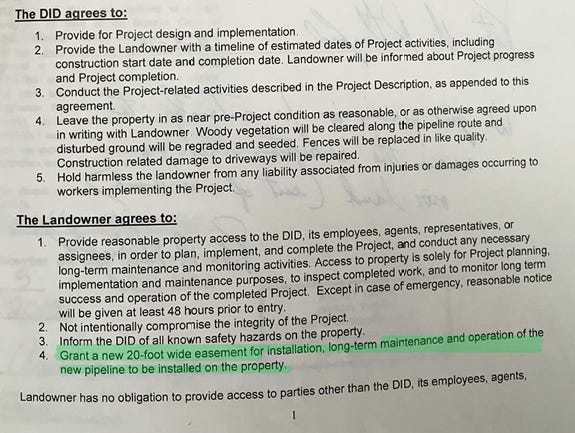

Irrigation ditch shareholders who embrace the piping project, and are willing to modify the existing easement, must sign a “Landowner Agreement.” This agreement provides the CCD and SPTIA the authority to enter the landowner’s estate with heavy machinery to remove vegetation, excavate trenches, and install pressurized pipelines.

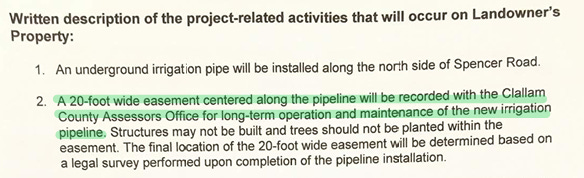

The landowner agreement drastically changes the easement. Instead of “10 feet on both sides of the ditch for maintenance” the easement has been changed to read “a new 20-foot-wide easement for installation, long-term maintenance, and operation of the new pipeline to be installed on the property.”

By agreeing to the new easement terms, landowners also agree that the easement for a ditch is abandoned and a new easement for a much more invasive installation of a pressurized pipeline through their property is authorized.

Not all landowners agreed, and tensions grew among some shareholders when they perceived that SPTIA and CCD were piping Sequim’s original irrigation ditch without the legal authority or consent of private property owners. The two agencies were accused of ignoring mounting concerns over wildlife habitat loss, safety, and water rights. In what seems to be a lack of transparency and communication from the county, the old SPTIA board (in favor of piping) was ousted, and new directors were installed on February 12, 2024.

According to the meeting minutes, the new directors immediately planned to withdraw the SPTIA Memorandum of Understanding with the County and also planned to “cease any piping project for which there is not unanimous shareholder and/or landowner consent for a piping easement. In addition, to the lack of consent to enter into piping easements, there were shareholders who expressed a desire for more studies as to the long term impact of the piping easements on upland habitat (wildlife, tree canopy) and aquifer recharge before any additional piping is done.”

The reorganization of SPTIA is troubling for Clallam Conservation District Manager Kim Williams who announced at the commissioners’ February 26th work session that, “the future of irrigation piping in Sequim might be at risk right now.” (The meeting can be viewed here by advancing the video to 1:44:30).

"We're this tiny subdivision of government having to comply with all the open public meetings act and all the government rules and stuff. It's been a challenging year," Williams told the commissioners. "Right now, the irrigation work is taking a lot of my time.” About 30%-40% of her time, Williams estimates, is dedicated to irrigation issues and the public records requests that accompany it, but she doesn't mind. "We are a subdivision of government; we are open and transparent. We want to communicate better."

“I believe there could have been better outreach and knowledge to all the landowners involved about what’s happening, what’s going on,” admitted Williams. When Commissioner Johnson asked which irrigation company had a new board, Williams answered, “The Sequim Prairie Tri-Irrigation Association, SPTIA, and they had their annual stakeholders meeting, and this group of landowners, they’re trying to stop this project, this $2.3 million project that we have funding for, that we have partners, I don’t exactly know what happened.”

Similar to the funding that was funneled away from surfacing Towne Road, it seems that grant dollars allocated to pipe Sequim’s original ditch are set to expire.

Williams acknowledged that some landowner concerns are valid. “There will be some loss of vegetation when the pipes go in and the recharge, or loss of water to groundwater, whatever you want to call it. Is that the intended use of the Dungeness River water? That’s what we need to think about. Is it to water the trees along the irrigation ditch? Is that the proper intended use?”

That is the debate: private property owners have established rights about who and what is allowed on their property. Shareholders paid for their shares when they bought their property, and they were (and are) taxed and assessed on those shares. Landowners have paid for the use of water on their land as needed and they have the right to water the trees and plants along the ditch and beyond. Landowners with wells have water rights, and the piping of ditches jeopardizes the performance of wells. The county, through the CCD, appears to be overreaching its authority in an attempt to determine how rights held by private property owners shall be exercised.

A desire of Clallam County leadership, often mentioned during commissioners' work sessions and meetings, is to participate in robust community engagement. Be it the pledge to involve the community of Dungeness in the future of Towne Road, or the assurance that the public's concerns will be considered about permitting tiny homes, the county has been clear that this goal of public involvement can only be achieved when all "stakeholders" are engaged. However, the mechanism for such engagement is not in place.

Robust community engagement would suggest an opportunity for the community to ask questions of their county government and receive answers. One only needs to attend a single commissioners’ meeting on any given Tuesday to know that this isn’t true.

Public comment during the commissioners’ meetings is restricted to three minutes per person and occasionally the entire public comment period is restricted to one hour. The comment period only allows the speaker to address the commissioners, not for the commissioners to address the speaker. In other words, questions may be asked, but there is no obligation that the commissioners provide an answer (and they rarely, if ever do).

This paradox of “robust community engagement” results in many of the same questions being asked week after week while the commissioners sit silently, keeping an eye on the three-minute timer. When the meetings adjourn, the commissioners may exit through the back door while avoiding the gallery where the public is allowed to sit. The entire policy of robust community engagement is completely voluntary, and it depends on the individual commissioners’ desire to participate, or not, during public meetings.

According to CCD Manager Williams, robust community engagement seems to be on the horizon. She closed her meeting by suggesting, “We should schedule a more in-depth presentation about irrigation.” Commissioner Ozias was quick to reply. “Yes, but I think we probably want to think a little bit about exactly what the focus should be.”

Those who attended the Towne Road informational community meeting at Carrie Blake Park last September know how Commissioner Ozias focused the conversation. The event was advertised to solicit discussion but focused on banning oral comments. While the recreational advantages of a closed or restricted Towne Road were focused upon, the knowledge that emergency response times would increase and that homeowners’ insurance rates would more than double, was omitted. While Commissioner Ozias focused on the community’s belief that it could weigh in and determine the fate of Towne Road, decisions had already been made to install electronic, automatic, Taxpayer-funded gates that would ban all but a few residents from using the public county road.

Like the Towne Road saga, how Clallam County chooses to address the concerns of irrigation shareholders and residents will be seen as either building trust or eroding it. If the county continues to embrace the culture that prevented the Happy Valley Gravel Pit from following due process, and if the county welcomes special and private interests instead of the transparency, honesty, and accountability that benefit the greater community, much more will be lost than Sequim’s first, and last irrigation ditch.

In Sequim, accountability enables trust, leadership grows confidence, and water is wealth.

The following opinion editorial was written by Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe chairman/CEO W. Ron Allen and was published by the Peninsula Daily News on Saturday, February 24th, 2024

Good stewardship for future generations

IT IS A tribal saying that “Every River Has Its People” and the Dungeness Watershed has been the home of the Jamestown S’Klallam and their ancestors for thousands of years.

Newcomers have been arriving since the late 1800s, settling in the Sequim-Dungeness area, sharing the benefits and stewardship responsibilities.

In 1855, S’Klallams reserved the rights to fish, among other provisions essential to our continuation as an indigenous people preserved in a treaty with the United States, which is recognized in Article IV of the constitution as Supreme Law of the Land.

An early water right adjudication (1924) provided for irrigation diversion from the Dungeness River at approximately five times the usual summer flow, with no minimum instream provision.

In the following decades, it became obvious that this water right depleted the river and its aquatic resources. Salmon runs plummeted and the S’Klallam could no longer fish on our prized Chinook.

Before the Chinook, summer chum, bull trout and steelhead stocks of the Dungeness were listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), our Tribe was already committed to recovering Dungeness salmon – We are Salmon People and honored to preserve a resource that is essential to our way of life.

Instead of fighting in court, our Tribe wanted to work with our neighbors and community for a common cause.

Cooperation among the Tribe, Irrigators and Washington State resulted in a water trust agreement between the Irrigators and the State to facilitate long-term water conservation.

The agreement commits the water users to diligence in conserving water and keeping their delivery system efficient, recognizing that every cubic foot of river flow is precious.

This cooperative water management tool was awarded recognition by the Washington State Governor and the President’s Council on Sustainable Development.

It is important to share this history and recognize the years of challenging negotiations to find common ground on responsible stewardship.

Irrigation canals are not streams or wildlife corridors; they are water conveyance structures designed over 100 years ago, to provide water for our agriculture community in dry summer months.

When canals are not enclosed, they leak, literally draining the flow of the river and reducing instream habitat.

Both salmon health and community agricultural viability rely upon responsible water conservation.

Clallam Conservation District (CCD) has voluntarily assisted the Irrigators with implementation of outstanding water conservation and efficiency projects.

It is disappointing that a small number of landowners are obstructing this process.

While it is understandable for unaware landowners to desire a surface water amenity, it is a mistake to maintain private benefits at the expense of agricultural and tribal resources.

My hands are up to the community for its progress in water conservation.

We have been an example to others seeking a constructive alternative to litigation.

Our hands are up to the Clallam CD and irrigators, for your progressive initiative.

The leadership of our community must remain committed to collaboration, conservation, and partnership as we adapt and struggle with climate-related stressors.

At the end of the day, we must be accountable to our future generations as good stewards of natural resources essential to our wary of life in our Sequim/Dungeness Valley.

Thank you Jeff for keeping the community updated.

Thanks, Jeff. I feel I am getting caught up with the water situation that John and Victoria have been commenting on during the Commissioners Meetings.

Notice how Ron Allen used the word "Newcomers" in his article. I'll be there on Tuesday! And Saturday!