Is temporary housing the permanent solution?

County approves $4 million for luxury homeless apartment complex

Dishwasher debate debunked. Not enough housing, or too much? A local nonprofit is rethinking the traditional approach to solving homelessness, but there's a catch: nobody will be getting rich.

Peninsula Behavioral Health (PBH) recently broke ground on its 36-unit luxury permanent housing facility for the homeless in Port Angeles. CEO Wendy Sisk assured the Peninsula Daily News that if funding doesn’t come through, there are “backup plans on backup plans on backup plans.”

One of those backup plans was revealed on Tuesday when Clallam County Commissioners unanimously agreed to approve the $4 million that had been previously secured. The four-story building, estimated to cost $12.75 million, will feature a rooftop terrace, water and mountain views, and a dog washing station.

However, PBH still needs your help.

Your donation of $100 could fund:

One-fifth of every dishwashing machine that will be installed in each unit.

0.028% of one apartment which costs, on average, $354,166.

0.04% of the CEO’s $250,967 annual compensation.

“This is on the low end of where costs are,” the County’s Housing and Grant Resource Director Timothy Dalton assured the commissioners earlier this month. He explained that projects like this average $375,000 to $500,000 per homeless housing unit in our state. He blamed much of the cost on state mandates that require solar panels and EV car charging stations.

“I’ve gotten some heat for including dishwashers,” Sisk admitted to the commissioners. In May, the dishwashers were promoted as a way to remove barriers to success, but that has changed. “Dishwashers produce far less wastewater, and the City did have some concerns about wastewater capacity in that neighborhood,” Sisk clarified last week.

The new 4-story facility will be built on the site of former PBH housing. The old buildings were deemed inadequate for homeless housing due, in part, to a rodent infestation. The two former PBH buildings were moved across the street and will serve as homeless housing for Oxford House.

“Could we have built a big block, square thing on the lot with more? Yes, but I feel that 36 is pretty high density,” said Sisk when asked what methodology was used to arrive at that number of units. “36 felt like the maximum that we could provide support to people to in that building effectively,” she further explained.

In other words, building more than 36 units would stretch PBH’s resources too thin. The IRS Form 990 for PBH shows that 184 employees worked there in 2022.

“There have been a couple of apartment buildings on the market recently. Instead of building this new apartment building, why don’t we just buy something existing? And the reason for that is it doesn’t create anything new; it doesn’t solve a problem. We then have to displace folks who are maybe in market-rate housing, and that’s not a solution that we’re willing to participate in. Our housing opportunities cannot be at the cost to the rest of the community because we have a housing shortage at every level,” Sisk said.

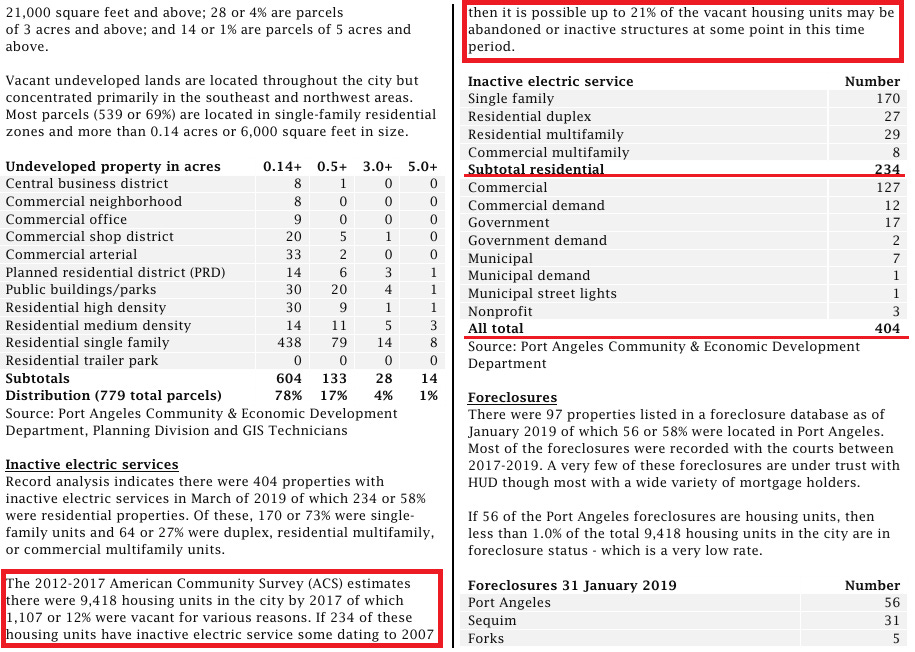

Data from a 2019 City of Port Angeles “Housing Action Plan” suggests there’s plenty of empty housing. In 2017, 12% (1,107) of the City’s housing units sat vacant.

The homeless industrial complex

Construction of the North View building is controversial for several reasons:

The facility is “not exclusively dry,” meaning drug and alcohol use will be tolerated.

PBH’s recent housing project, Dawn View Court, exceeded construction estimates by 37%.

Residents may live in North View as long as their income doesn’t exceed the threshold, and PBH measures success by having zero turnover. This model disincentivizes self-reliance.

Housing will be prioritized for those who are at high risk of incarceration.

Every person struggling with addiction or seeking housing has a dollar sign hovering above their head. Once a path toward independence is found, sometimes through temporary or transitional housing, that dollar sign is replaced with self-reliance. With permanent supportive housing, clients can be a conduit to fund the agency’s drivers, therapists, peer support specialists, case managers, admins, billing specialists, and CEO for years.

Wendy Sisk’s $250,967 compensation grows as our homeless problem grows (Sisk received a nearly 6% raise from 2021 to 2022). If the homelessness problem improved, some 184 PBH employees making a combined $12,301,400 annually could be let go (their compensation grew by 7.2% from 2021 to 2022). For community leaders who enjoy their titles but not necessarily their duties, donning hard hats and turning that first shovelful of dirt at a construction site boosts egos and opens political doors.

"Government bureaucracies and nonprofits often prioritize their own survival over truly helping the homeless." - Edward Ring

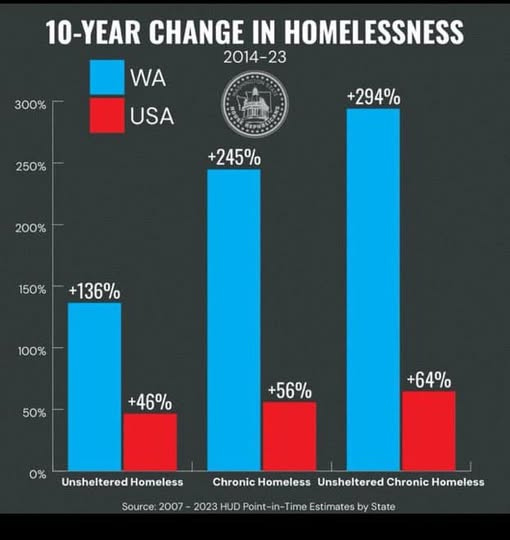

Despite increased investment in permanent supportive housing, the number of unsheltered homeless individuals has risen.

Implementing permanent housing solutions is expensive when funds could be better allocated to other services that reach more people or temporary models.

Simply providing permanent housing without addressing underlying issues prolongs the problem without solving it.

There’s an alternative.

Milestones will be celebrated

“There hasn’t been a ‘hardest day,’ but there have been ‘hard moments,’” answered Joe DeScala when questioned about his past three years as director of 4PA, an organization he founded to clean up his hometown and help its homeless population transition to self-sustainability.

“It’s hard to go back to the same place we just restored and do it all over again. Or worse, seeing people continue their old habits. It’s truly heartbreaking seeing people at their lowest,” says DeScala. However, he’s adamant that the good days outweigh the bad.

“The other day, I was talking to Dan and seeing the change in him — it’s huge.” Last March, DeScala connected with Dan through a referral from a partner agency, Olympic Peninsula Community Clinic (OPCC). Dan was homeless, and 4PA hired him as a cleaning crew lead.

“When I met him, he was pretty quiet, but I could tell he wanted to improve his situation through work and gaining purpose.” DeScala says that as Dan realized his self-worth, he spoke up a lot more, and his smile returned. “It seems to me he stands up a bit taller now.”

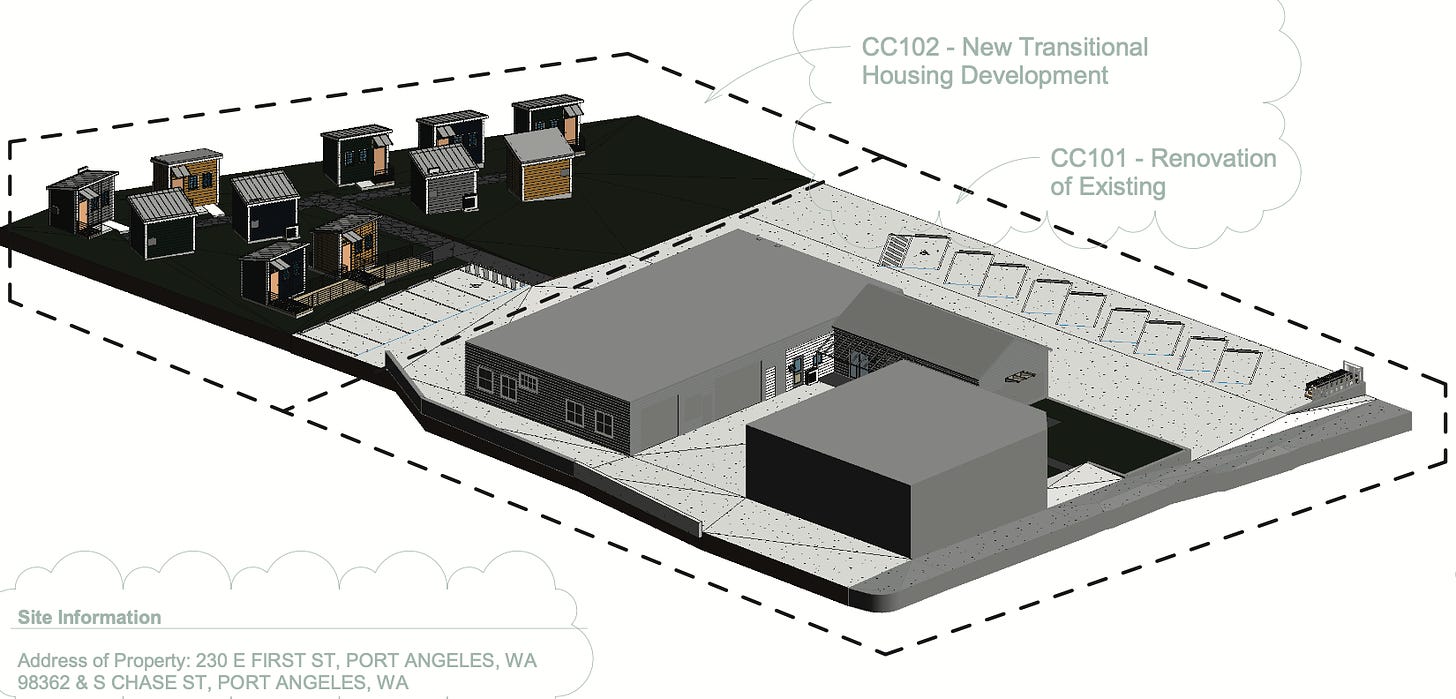

Dan currently lives in his van and will be the first resident to move into 4PA’s planned Touchstone Campus, an 11-unit temporary housing project behind the organization’s offices on First Street in Port Angeles. Dan believes that if he can be sheltered for just a year, he will have time to focus on becoming self-reliant. He'll continue working and become the onsite manager for Touchstone’s 11 tiny homes.

Touchstone will be more than just housing; DeScala sees it as a community asset with a public area, murals, a food truck court, and a storefront where residents can learn business management while manufacturing and selling goods. The entire project will foster a connection with the community. “Milestones will be celebrated as people advance, and it’s critical we give back to the community,” DeScala said.

“We’re not ready to say yet, but the business we start on-site might have something to do with creating a food product that we can turn around and sell locally,” DeScala hinted. The product will be manufactured at 4PA’s offices, the former Lannoye Motor Company’s building, a half block east of Lincoln Street on First.

Each shelter will be an 8’ x 12’ shed with heat, power, and a lockable door. One of the 11 homes will be ADA-accessible. The tiny homes won’t be plumbed, but steps away, 4PA headquarters will have a common space with a kitchen, bathrooms, laundry, and showers.

High barrier housing

“You have to have skin in the game,” says DeScala. “The most successful outcomes I’ve seen are when people are held accountable and are expected to give back to the community that is helping them. Even if it’s just a little bit at the start.”

Residents will wash dishes, clean common areas, and work in 4PA’s sales and manufacturing to earn income and learn job skills. DeScala says the campus will be high barrier, meaning drugs and alcohol will not be permitted. “I believe in second chances, of course. However, if someone is caught breaking the campus rules, an exit plan will be in place — hopefully into treatment. I’m just not willing to compromise the success of our other residents.”

Touchstone’s target is to house a resident for up to one year. During that time, 4PA will work with the resident on stability and job opportunities until self-sufficiency is achieved. “This will be done in conjunction with our partner agencies like OPCC, PBH, and NOHN (North Olympic Healthcare Network) acting as case management. I’m not shy in saying that we will be relying on professionals outside of 4PA for help in this process. I’ve always seen us linking arms and working with other agencies.”

Part of the homeless industrial complex?

“I didn’t set out to be collecting garbage at age 49,” said DeScala. “I don’t want to clean forever. My goal is to help my community, and I look forward to the day the cleaning aspect of my job is done. And when I say ‘community,’ I mean everyone in it.”

Last year’s IRS tax form 990 showed 4PA’s total revenue was $306,485, and expenses were $165,973. The organization spent $106,966 on employee salaries for five people. Two employees are unhoused (including Dan, a crew lead), and another lives in a women’s shelter. They all work part-time to help clean abandoned encampments and restore city properties. A part-time administrator is also paid; she is housed. The fifth employee, DeScala, works full-time. The model for his nonprofit puts 30% of expenses into the pockets of his employees transitioning to self-reliance.

DeScala believes strongly in transparency, and 4PA’s Form 990 is available to anyone upon request.

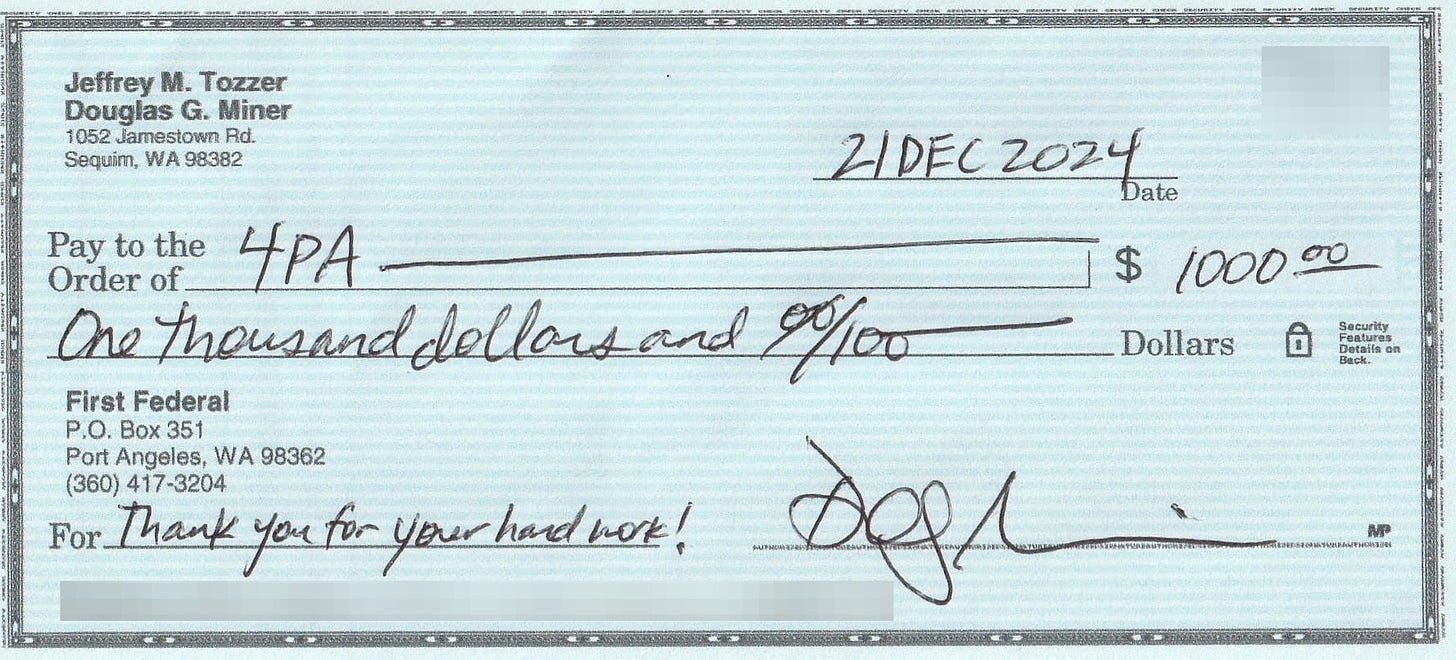

4PA is funded 100% by community donations and receives no federal, state, or county money. The nonprofit just received $25,000 from the First Fed Foundation, and the City of Port Angeles covers their dump fees, an estimated $30,500 so far. DeScala says 4PA has removed over 250,000 pounds of garbage from abandoned homeless encampments and illegal dumping sites. “The generosity of our community to support our efforts with pledges has been nothing short of amazing.”

“On the flipside, finding grant money is proving to be a bit more difficult,” admits DeScala. “Most funding agencies don’t come up to you and say, ‘We have money.’” While that may seem challenging, DeScala says it’s a benefit too. “When certain agencies give money, they often get to dictate how things go. This way, with private funding, we can follow the model we believe is most successful.”

Despite presenting this project during public forums, DeScala hasn’t been approached by anyone in County government about his housing model. “$2 million would build our entire campus, including the 11 tiny homes. It would pay off our building and cover two years of operating costs.” The tiny homes, combined with renovating the old car dealership, are estimated to cost $1.3 million, 20% of which has been raised.

Challenges

DeScala says PBH has definitely added to 4PA’s success and is excellent at connecting people with services. He routinely attends partner meetings with PBH, OPCC, and the Port Angeles Police Department. Information is shared to determine where homeless people can be found, and strategies are devised to best help them. For example, if 4PA’s team finds an encampment but doesn’t know who lives there, one of the partner agencies might have that information.

In addition to the generosity of businesses and residents, plans for a tiny house village have been well supported. However, there have been some misconceptions about what 4PA does.

“There are inhumane ways to clear camps, but we don’t do that here,” DeScala explained. Unfortunately, theft and crime can be frequent in encampments, and sometimes 4PA gets blamed for the property destruction. “Our routes are scheduled and publicly posted. Often, we weren’t in an area we’ve been accused of damaging, and we follow a strict protocol if we come across personal items to ensure they are not discarded.”

Looking forward

“Once it’s built, we’ll be recruiting volunteers to teach trades, give cooking classes — that’s what I’m most excited about. Right now, and I hate sounding like a broken record, we need funding.” DeScala says the average cost per tiny home is $30,000. That price may drop due to support from the business community — Hartnagel Building Supply and Angeles Millwork have been generous in donating building materials. 4PA runs a “Tiny Home Tuesday” update on its Facebook page and recently announced that 80% of its 5th home has been funded.

“Come see what we do. If it isn’t for you, I get it. But if it’s something you believe in and support, and if you pledge to 4PA, that means I’m accountable to you. I want you to get a return on your investment. I grew up here, and I know how good PA can be. I’m doing this for you and our community.”

If you’d like to learn more about 4PA or donate, visit their website at www.4PA.org. Their mailing address is 4PA, PO Box 25, Port Angeles, WA 98362, or email info@4pa.org.

Last week, subscribers were asked which transportation projects WSDOT should prioritize. Of 237 votes, 1% chose replacing culverts, 11% chose installing roundabouts, and 88% chose repairing Highway 112.

Dang! Those luxury apartments have more amenities than most of us middle-ish class, who work and still struggle to make ends meet. Air conditioning, dishwashers, dog wash stations, rooftop terrace…wow! And did I read correctly, solar panels and EV car charging stations?? Seems more likely an enabling environment to me…what an incentive to not work, lest you exceed the income guidelines, you lose out on luxury. My crystal ball tells me this won’t end well.

The 4PA housing seems more likely to be helpful to those who want to get back on their feet, seemingly without enablement and without taxing the hell out of city/county residents. We need to support this model in our community and reject PBH’s frivolous ‘Daddy Warbucks’ model.

You cover many topics, but what I don't want to lose sight of, when the discussions devolve into the topic written about, is that we have 3 Commissioners who are the root cause of the problems this county faces.

Using a few Lean manufacturing techniques, designed to fix things when they've failed, root cause would ask to identify why the problem has occurred (ultimate blame/responsibility). For every article you write, each time I blame our Commissioners.

I would then apply the same root cause question as to why they fail us in so many ways, and absent other information I come to the conclusion that they see their actions as a way to stay in office and meet their personal needs over the needs of the county's residents.

I don't blame those who know how to exploit our Commissioners, they're just doing what our elected officials let them get away with. Our Commissioners are patsies for the people who know how to manipulate them.