What happened over the last thirteen years to cause Clallam County’s pronounced economic underperformance? Once on par with Washington State, Clallam County, at one time, outperformed the United States and neighboring Jefferson County. However, since 2011, Clallam County has done nothing but tread water while the metrics of other counties, the state, and the nation have steadily grown.

Put simply, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is what a jurisdiction (like Clallam County) produces over an amount of time. GDP is a commonly used marker of economic health: it tracks the economy’s change in size, measures an area’s economic prosperity, and it can provide insight into factors that are either growing the economy, or holding it back. When viewing GDP growth on a global scale, the United States and China are at the top – these two countries are making products that consumers want. Argentina, Libya, and Syria are examples of countries with declining GDP. In terms of stagnant GDP growth, Ukraine is a good example.

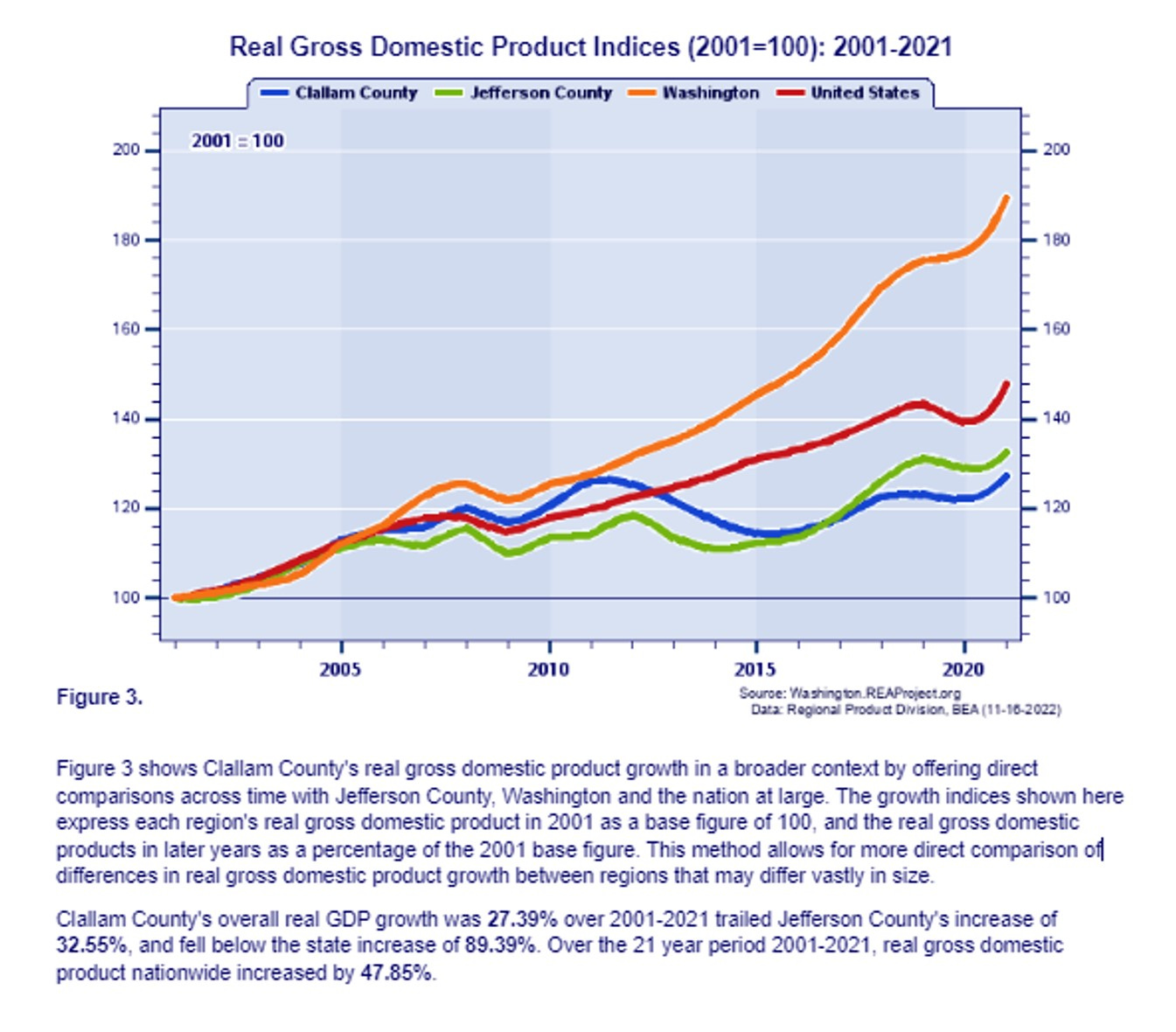

The chart below generated hundreds of comments when Clallam County resident Steve Pelayo posted it to “The Real Port Angeles” Facebook page.

The graph shows GDP growth starting in 2001. You can see the United States’ GDP (red) has grown steadily over the past two decades. Washington State (orange) has grown consistently and dramatically. Jefferson County (green) lagged behind Clallam County until 2017 when we were outpaced for good. Clallam County (blue) began the century with positive growth, and even did better than the national average starting in 2007, but after that “blue hump” in 2011, a decade of undulations has kept its pace idle. Available GDP data shows Clallam County is in the same position as it was in 2011. That’s 13 years of growth for our nation, state, and even sleepy Jefferson County next door, while Clallam County has done nothing but perch on the edge refusing to take flight.

Clallam County is an anomaly in that it’s the only county in the United States to have an elected Director of Community Development (DCD) – every other county appoints their DCD director who works under the guidance of the County Commissioners. In the early 2000s, some in Clallam County were dissatisfied with the appointed director of the DCD but insiders couldn’t figure out how to get rid of him. Thus, it was decided to change the job to an elected position.

A possible telling indicator of the GDP decline, Sheila Rourk Miller, the third elected DCD director of the county, assumed office in 2011. As a code enforcement officer, she had spent two decades working her way up through the department. Challenges abounded during her four-year tenure.

Washington State legalized marijuana production and growers were eager to build greenhouses in Sequim’s sunny “banana belt.” A litany of meetings with the Board of Commissioners, to navigate the Conditional Use Permit (CUP) process, consumed much of her department’s energy. Residents, unhappy at the prospect of living next to, or even in the same county as a marijuana farm, leaned on the commissioners to deny the CUPs. The commissioners, who set the salary of the DCD director, influenced and pressured the DCD to reject permits. Small business owners faced a nightmare: grow operations that had been initially approved and had invested heavily in infrastructure saw their ventures unexpectedly rejected when Roark Miller scrambled to please the commissioners. Sensing that the DCD director was now beholden to voters, picketers crowded the sidewalks in front of the courthouse. Bickering began in earnest between the commissioners and the DCD, emotions overruled guidelines, and decisions were delayed in all areas of county government.

Clallam County’s GDP peaked in 2011 but when Rourk Miller became entangled in dealings with the marijuana industry, it took a nosedive. The gridlock had begun.

The Department of Ecology’s Dungeness Water Rule went into effect in 2013 causing uncertainty for people who wanted to build and drill wells in eastern Clallam County. The Water Rule also established senior water rights for existing wells – the DCD became inundated with a rush of applications for well drilling permits that had to be processed before January 2, 2013. Understanding that applicants had followed due process, and that her department had delayed approving the permits, Rourk Miller interpreted a Washington Code that allowed her to backdate permits to reflect that they had been approved when they were submitted weeks before. A whistle-blower within the county reported Miller for altering and destroying documents as well as falsifying records.

An investigation ensued and a report was completed. In what may have been the greatest contribution to the collapse of the county’s GDP, the Clallam County Commissioners refused to even read the report. This began a new standard among Clallam County’s elected officials who would not even engage in discussion of each other’s actions regardless of the repercussions to county government’s credibility. This culture persists today, and without any internal check or balance of this behavior, the power of Clallam County’s elected officials can be elevated for personal benefit with immunity.

Rourk Miller spent the end of her term embroiled in a legal fight. While the national GDP strengthened for four straight quarters in 2013, the overseers of Clallam County’s economic engine were focused on internal strife. The embattled Rourk Miller fought legal attacks and the county’s GDP continued to decline.

Mary Ellen Winborn defeated Roark Miller and assumed the DCD director role in 2015 – note the uptick of the blue line as Clallam County’s GDP began to grow again. Winborn, an architect, brought more diversified qualifications to the job. The GDP of Clallam County grew during Winborn’s first term, and she won her second term, in 2018, by a landslide.

Then the pandemic hit. Winborn wanted to work remotely, but the DCD shared a floor with the Road Department who wanted to continue working in the courthouse. The Commissioners wanted to keep the courthouse doors open to the public, Winborn did not. Tensions rose. Local government was understandably strained, and personality conflicts strained operations further. There was a disagreement about masking protocol, and who had privileged keycard access through a side door. Unnecessary obstacles abounded and, once again, county leaders lost focus on making economic gains for their constituents.

During this internal struggle, county leadership began to implode. The $20 million Dungeness Floodplain Restoration Project began in an environment of unknown, everchanging directives that continue to plague the project today. The destruction of an existing dike, before the new levee’s completion, was the result of abysmal communication between the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe (who breached the original dike), Clallam County project leadership, and the Army Corps of Engineers.

This initial chaos occurred under the supervision of Director Winborn. The void of leadership fostered a culture where the elected officials of Clallam County prioritized personal battles and agendas over the needs of taxpayers and county business. What is now called the “Towne Road Levee Setback Project” became a field day for private and personal interests, including the top donors to our elected officials’ campaigns.

Winborn’s critics finally caught her on a technicality when, in May of 2022, she moved to Mississippi. The agreement was that she work remotely and visit Clallam County once a month, but Clallam County sued their DCD director and imposed an injunction that prohibited Winborn from serving in her role (while still paying her full annual salary of $101,000).

Currently, the DCD is led by Bruce Emery who took elected office at the beginning of 2023. Rather than relying on the policies and guidelines that would guide someone in an appointed position, he has the unenviable task of filtering his decisions through the lens of what the electorate wants. One clear example is the continued debacle that is the Towne Road Levee Setback Project.

After millions of dollars, decades of planning, and multiagency involvement, Director Emery entered his new job with the end of this massive infrastructure project in sight. However, despite the project being designed and funded to completion, a distraction surfaced: 98 residents, who had grown used to Towne Road being a low-traffic cul-de-sac during the road’s temporary closure, wanted to keep the traffic away from their neighborhood (even though the project plan had specifically stated that Towne Road wouldn’t be closed for even one day). Additionally, a donor who would fund over half of one commissioner's upcoming campaign, also wanted the road to remain closed. These powerful influences began to pressure Commissioner Mark Ozias who halted the project.

Despite the results of a 2015 public survey, where 83% favored that the road remain open, and despite 140 signatures submitted to the county supporting an open Towne Road, the goals set forth at the beginning of the project were scrapped and Director Emery was persuaded by the Board of Commissioners to stop the project’s completion.

With the project interrupted, Director Emery set forth to sample public opinion for a third time. What should have been conducted as an unbiased collection of data had all the hallmarks of a campaign with a preordained outcome. The DCD mailed notices to only a fragment of the community that was affected by the road’s closure and signage was limited to the levee where walkers, not road users, were most likely to see and learn of the possible change. Still, it was the “informational meeting” held at Carrie Blake Park in the fall of 2023 that was most unsettling.

The meeting, which drew hundreds of inquisitive residents, was billed as an opportunity to “solicit discussion” about Towne Road’s fate, but oral comment was not allowed. While the DCD and Commissioner Ozias promoted recreational benefits, the county didn’t share that the road’s closure could cause home insurance rates to more than double in Dungeness, or that emergency response times could increase by three to seven minutes. The DCD outwardly messaged that tsunami route designation was being sought, but they hadn’t even taken the first steps. Despite Washington Emergency Management Division’s Tsunami Program Coordinator writing, “There are no formal requirements for what constitutes an evacuation route,” and that, “ANY road or route that gets you to safety is an option,” the county continues to waffle on the road’s possible evacuation route designation.

When results from the 2023 public survey was processed, data clearly showed 55% of those favored an open road and 45% favored a closed road. Curiously, at the recent Port Angeles Business Association meeting, Emery discussed the survey results by saying “it was evenly split.” He also remarked that, “there was some misinformation floating out there that the board was thinking about only doing the trail and it’s like, no, no, it’s always been this option.” Emery’s own department proposed “option 4” which would have converted the public road into a private driveway, closing it to through traffic forever.

The mismanagement of Towne Road can be traced back to Winborn’s tenure of overseeing the project while she worked remotely from Mississippi. In her absence, Cathy Lear, who still works in the DCD, oversaw management of the project. Lear, the county’s habitat biologist, was in charge of managing an infrastructure project and the funds associated with it. Lear’s priorities refocused on flood restoration instead of infrastructure, and funds were reallocated from surfacing a road to removing reed canary grass.

To this day, a comprehensive budget of the $20 million Towne Road Levee project remains difficult to obtain and is unavailable from county records. The budget has been requested of four county leaders, across three departments, and the only indication of its existence has been a response from Director Emery, “I am working on a response to your request.” In the aftermath of a grossly mismanaged project, and amid efforts to promote accountability and transparency, the spreadsheet that shows “money in, money out” seems elusive or may not exist at all.

What does Towne Road have to do with the county’s GDP? Not only does keeping roads open support commerce by transporting goods and services, but maintaining rural routes promotes economic growth. In 2015, the owner of the Dungeness Valley Creamery conveyed their fears to the county if the road were to close. “There is less cost associated [with] delivery and distribution where we have the factor of wear and tear on vehicles, insurance, wages, fuel, and other miscellaneous expenses,” he said. “This leads to higher margins for these particular sales, which we rely on for our operations and success of our business.”

Another example of GDP being directly affected by the whims of the DCD director is the Happy Valley gravel pit. At first, when a landowner proposed reopening a dormant, family-owned gravel pit in 2023, a “Determination of Non-Significance” was issued under the State Environmental Policy Act – no adverse impacts were foreseen if the 4.74-acre gravel pit were to reopen, and the project was greenlit. Neighbors of the gravel pit, including Commissioner Ozias, pressured the DCD’s hearing examiner to reject the permit but she didn’t get the chance – the family received threats to their home and business and the application was withdrawn. With that, four full-time, family wage jobs disappeared from Clallam County, as did the gravel pit that would have supplied Clallam County directly.

The DCD’s message seems to support a stagnant GDP: we want gravel, we just don’t want the gravel pits or jobs that come with it. This philosophy is evident in the cancellation of the Power Plant timber sale, and the proposed land swap that would see tax dollars flow to Clallam County from the harvest of timber land in Wahkiakum County. Again, our county leaders have voiced: “We want the lumber and the money, we just don’t want the loggers, foresters, truckers and surveyors who, by default, are renters, homeowners, and shoppers in Clallam County.”

A year into his tenure, we can begin to gauge how Bruce Emery will be leading the office of the only elected DCD director in the nation. One of the cornerstones of Emery’s campaign was code enforcement. The county adopted a memorandum in April 2023 that required the DCD to provide quarterly code enforcement updates and reporting – but the first report came nine months later in January of 2024. “My bad,” Emery offered as an explanation to the report’s six-month delay. 2023 started with 344 total open code enforcement cases and ended the year with 345. Cases are open, on average, 460 days. In other words, if a neighbor is blaring loud music or has a faulty septic system, and if the county were notified of that violation today, that complaint, on average, would be resolved by May of 2025. Emery’s department is currently awaiting payment of $250,000 in delinquent fines from two specific cases.

During the director’s January 22nd presentation to the commissioners and the public, Emery supported the success of his code enforcement team by saying, “we had seven cases go to the hearing examiner.” After a search of public records showed zero cases had been brought before the hearing examiner last year, Emery clarified by saying, “Although seven cases had been scheduled for review before the Hearing Examiner, upon further review, no cases were actually heard by the Hearing Examiner.”

Can Clallam County, by being the only county in the nation to elect its DCD director, be credited with taking a bold step that 3,243 other U.S. counties have not? Doesn’t having an elected DCD director allow “the people'' to have a say in the direction that their county is heading? Are there any negative consequences? There are, and concerns were brought before the Charter Review Commission in 2002 when the notion of making the DCD director an elected position was being proposed. “I can’t imagine a situation where the Director, who should be balancing all sides on an issue, could be a partisan elected official and not carry that bias into the hearing process,” wrote Frank Figg of Sequim.

Another concerned citizen wrote, “Changing this position to a partisan, elected position is, in my opinion, a big mistake. At first glance, it sounds good. I'm certain voters at the polls will think the same thing. But consider what you get once it's done. No longer will there be any requirement on qualifications. Elected partisan officials are not required to demonstrate any level of competence in a given field. The subordinate relationship between the director and the Board will also disappear. This means the position will no longer serve the same function as the elected Director will be free to pursue their own agenda, and yet only the Board will retain authority to adopt changes to ordinances.”

The individual who made the above comments in 2002 was Bruce Emery, the current elected leader of the DCD.

With the absence of a county-level board of ethics, or any ethical oversight that other municipalities have, there is no incentive for county leaders to conduct themselves in a transparent, honest, and accountable manner. It’s not illegal for the DCD to propagandize information, parting out selected data to the public while withholding crucial knowledge. It’s not illegal for a sitting county commissioner to use his elected office to halt a gravel pit next to his house and crush the dreams of a business owner who had visions of employing four people. These actions aren’t illegal, but they are unethical, and they are symptoms of a culture that is permeating Clallam County leadership.

Clallam County leaders know our economy is ailing. Commissioner French’s pet project, the “Recompete Pilot Program”, targets the hardest hit, most economically distressed counties with federal grant dollars meant to connect working-age people with jobs. Instead of fostering job growth and promoting small business right here at home, Clallam County intends to infuse the sluggish job market with qualified workers that, once trained, may find it easier to gain employment outside the county.

The symptoms of a stagnant GDP are reflected in shrinking enrollment numbers in school districts county wide. A family’s prosperity is uncertain when one’s livelihood depends on the desires of special interests and the personal priorities of county officials who use the elected power of their position to promote their personal agendas to the detriment of all other Clallam County Taxpayers. The business landscape of Clallam County is not for the faint of heart: an approved permit could be rejected, a business waiting to reopen could be indefinitely shuttered by petitions, a sitting commissioner may use his influence to close a business, critics of county government could be subject to criminal investigation and, a public road allowing commerce to reach a business could be closed and turned into a walking trail.

Civic engagement is to be welcomed and admired when bringing neighborhood concerns to county leaders, but Clallam County has developed a habit of inconsistently factoring public opinion when ruling on issues that have been clearly defined by proven guidelines. It’s enough to scare off all but the bravest entrepreneurs thinking about starting a venture in Clallam County’s not-so-free market.

The likes of gravel pit operators and loggers drive the economy. By outsourcing these jobs to other counties, Clallam County has less workers. That means fewer paychecks are being issued here — less fishing gear is being bought at Forks Outfitters, fewer families are shopping for school clothes at Swain’s, and Over the Fence has less foot traffic passing by its doors. When there is a reduction of money moving through the local economy, GDP loses its drive, and the economy begins to flounder.

Clallam County, via the ballot box, has decided what direction it will be heading – we want the products, we just don’t want to make them. The bad news is we aren’t China, the good news is we aren’t Libya, but we are performing about as well as Ukraine.

It would be totally unbelievable if we hadn't gained insight into the county's current philosophy regarding county business. Thanks for reading, Deborah... I miss you on ND and am so glad to see you here.

Excellent history of local corruption and incompetence. There is a saying, "People deserve the leaders they elect". Much of this incompetence is hidden from the public. This report is a step in the right direction toward educating the public, but alas, they are glued to their cellphones and will feel "TLDR" (too long didn't read) when it comes to the report. A successful campaign against the incompetence and partisanship would require succinct bullet-points, sign waving at intersections, billboards, and competent alternative candidates, before voting them out or even recalling them would be possible.

I feel the pain of all those affected, particularly the ever-delayed Towne Road completion. Remember, too, that the Tribe donates heavily against the project's completion. It is, indeed, painful and disheartening to see partisanship and corruption playing out in our communities, but until voters wise up and elect candidates with competence and integrity, nothing will change....except our taxes going up.