While Clallam County Commissioners cry budget shortfalls and slash essential services, they continue to pour taxpayer money into vanity projects, political favors, and pizza giveaways—leaving the very department that collects the county’s revenue unable to function. The hypocrisy is staggering, but the consequences are real.

“The farther behind we get, it begins affecting the tax base,” explained elected Clallam County Assessor Pam Rushton to the Board of Commissioners on Monday. “The load gets bigger, and we just don’t have the staff to provide the services.”

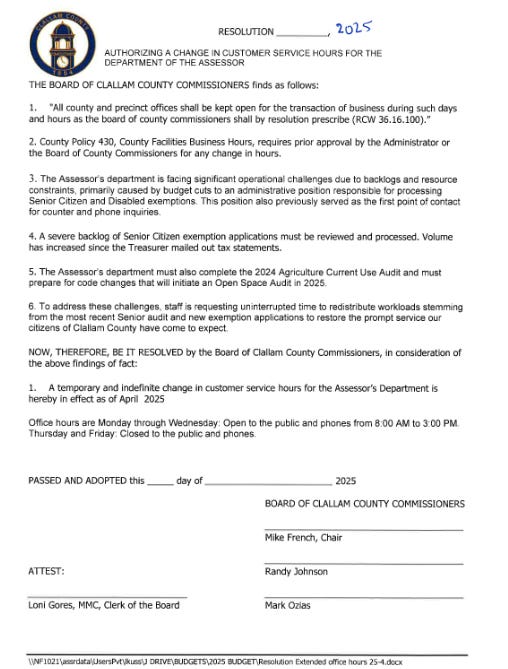

Rushton described how deep staff cuts, made in response to a historic budget deficit, have forced her office to close to the public on Fridays. Though her remaining team still reports to work, closing the doors allows them to focus on a mounting backlog—especially in processing senior exemptions. Rushton recently trained an employee to handle those exemptions, only to see that person laid off in the last round of budget cuts.

Now, she says, the office must remain closed to the public on Fridays—a temporary measure originally intended to end this spring.

Without adequate staffing, critical tax functions are stalling. If senior exemptions aren’t processed, elderly homeowners may receive inflated tax bills—errors that will take time and additional resources to correct. These aren’t minor inconveniences—they affect the very funding streams for schools, hospitals, and other tax districts. “Including you,” she reminded the commissioners.

“I don’t see getting caught up, we’re just buried,” said Rushton. “And the more buried you get, the more inquiries you get, so we spend a lot of time answering to people why their applications are not processed yet.” With appraisers pulled off their normal duties to help with processing, property valuations are now backing up.

Rushton bluntly admitted that her office is most productive when the doors are closed and the phones are off. “It’s just becoming more and more difficult to get our core government jobs done, and it’s affecting the tax base. That makes me very concerned.”

Commissioner Mark Ozias, attending remotely, chuckled as he offered, “It sounds like there’s certainly a mismatch right now between the workload and the skillset.” He asked what it would take to ensure that the assessor’s core function is executed.

“I think I’ve been very clear,” Rushton replied firmly. “We’ve been cut to the bone in our office.” She reiterated that they were already stretched thin before losing their only senior exemption specialist.

“It wasn’t a good idea to cut those positions. We were already running understaffed.”

Ozias laughed again: “We need to continue talking about it.”

In the assessor’s office, expenditures were already as low as they could be, Rushton said. “[Cuts] would have to be personnel,” she said. The assessor’s office lost its senior exemptions and audits administrative specialist. Now, Rushton said the workload will have to be redistributed to other people who already have heavy workloads. “I’m not sure how it is going to happen, everyone is already full,” she said. “It’s going to delay the process quite a bit.” — Peninsula Daily News, 12/14/24

Commissioner Mike French added, “I think our job is to serve the public,” expressing opposition to permanently reduced hours. “We all have to figure out how to do more with less, and that’s not going to change.”

“I don’t have the answers, guys,” said Rushton. “We just don’t have the workforce to do the work. And I would strongly suggest next year, when you’re looking at what I’m assuming will be further cuts, look at your core government jobs first.”

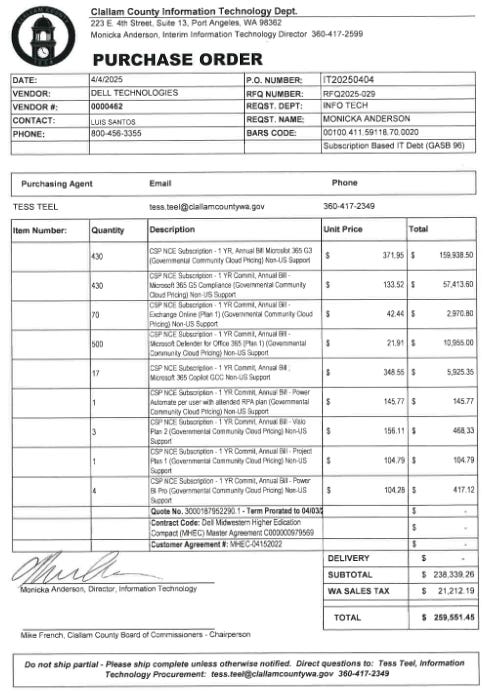

A quarter-million in software licensing

Immediately after Rushton’s plea, the next item on the agenda was a purchase order for one year’s worth of computer software licenses for all 450 county employees. The cost? $259,551.45.

Where has the money gone?

In other parts of the county budget, money seems to flow with little restraint—even as the very office responsible for generating revenue is collapsing.

The county spends $10,000 annually on pizza for the Harm Reduction Center in Port Angeles, which also distributes Narcan, needles, drug test strips, condoms, and drug paraphernalia.

A delayed Towne Road project led to a loss of full state funding, costing Clallam County $1.4 million.

$125,000 was allocated to the Olympic Peninsula Humane Society without any cost analysis or oversight—despite a 48% pay raise for the agency director.

$125,000 was promised to install electric gates to privatize a public road after the landowner agreed to host a campaign billboard for Commissioner Ozias (this effort stalled).

$120,000 was added to the Towne Road project for an unnecessary curb, pushed by Ozias.

$330,000 was redirected from Towne Road to the Jamestown Tribe to build log jams in a former cow pasture.

A $369,000 contract with Cascadia Consulting Group was signed without tracking payments, resulting in tens of thousands in unnoticed monthly outflows.

$4 million went to “luxury” homeless housing where sobriety is optional, raising concerns about the program's effectiveness.

$33,000 per parking space is being spent on a “safe parking” program.

A poet laureate was hired to perform in libraries and tattoo parlors.

Human trafficking signage

The county has installed multilingual signage in courthouse restrooms to help victims of human trafficking—at a cost of $5,000 for Phase 1. Phase 2, which includes wired panic buttons and braille signage, will cost over $13,000.

No one is arguing that human trafficking isn't a serious issue. But at a time when Clallam County cannot afford to keep its revenue office functioning, it's time to question the prioritization. Is braille signage in a bathroom, feet from the commissioners’ boardroom, more urgent than maintaining tax operations? Could the county survive without a poet on payroll? Could consultants be hired for less than $210 per hour to shop for electric gates?

Staffing crises and missed opportunities

In a December interview about the county budget, County Administrator Todd Mielke admitted to KONP Radio: “It’s about living within our means…”

But the reality is far from balanced. Earlier this year, a court-appointed attorney was “mistakenly excluded from the budget”—costing the county $521,860.

The Sheriff’s Office was forced to forfeit $68,558 in state funding for inmate chain gang crews due to staffing shortages.

A $100,000 courthouse security upgrade now aims to introduce airport-style screening, even as road maintenance and essential services remain underfunded.

The bottom line

Clallam County’s commissioners have managed to spend so freely that the department responsible for collecting revenue itself is starved of funds. This is not just poor management—it's reckless. The hypocrisy of asking departments to “do more with less” while quietly greenlighting unnecessary pet projects, overpriced consultants, political favors, and vanity programs is glaring.

The message is clear: Clallam County doesn’t have a money problem—it has a priority problem.